Following on from Episode 201 of the Martin Bailey Photography Podcast, I thought I’d post the transcript for Episode 190, in which I gave you ten steps to great long exposure images. So here goes…

Long Exposures can push a photographer and our gear a little out of our comfort zone, but they can also be a lot of fun. In April 2009 I was reminded of this when I did some long exposure photography over at a small harbor town called Ooarai, roughly translated as the Big Wash, in the Ibaraki Prefecture. I’ve been doing a lot of travelogue type podcasts lately though, so today I thought I’d move away from that and do a 10 step guide, but of course, interweave some of my real world example shots to make the points easier to understand.

Firstly, let’s make a distinction between Long Exposure and slow shutter speeds. I personally don’t like to use the term slow shutter speed in this case, because it’s pretty subjective. If you are shooting a flying bird at 1/60th of a second, this would be considered a slow shutter speed, if you were trying to freeze the movement of the bird’s wings, because it will be too slow to do so. It may not though be slow enough if you want to pan with the bird and create that beautiful sine shape made by capturing the wing movement. 1/60th of a second will also not be slow enough to make a large body of water smooth over into a dreamy blur. Anyway, let’s start looking at my 10 steps.

Step #1: Find a subject that will be complemented by a long exposure

As we get into Step #1, let’s bring up image number 1802, which will be on your screen now if you are listening in iTunes or on your iPhone, or you can view on the Podcasts page at martinbaileyphotography.com. So, the first thing you need to do, is decide on a subject that will be improved or have something accentuated by capturing it with a long exposure. It could be shots of fireworks displays, lightning strikes and car light trails. I’ve done all these, and have some example images, but maintaining my main nature photography theme, I thought I’d look at this landscape shot from almost a year ago, in Nagano prefecture here in Japan. I talked about it back in episode 141 as well. There are a few points that we’ll make while looking at this image, but the first, as I say, is finding a subject that will work with a long exposure. Your entire shoot doesn’t necessarily have to revolve around the Long Exposure shot. This image was very much opportunistic. But when I turned the corner on my way to the hotel, I saw the scene, and knew instantly that this would make a nice long exposure image. There were both heavy, textured clouds in the sky and a thick cloud layer in the valley, both of which would blur nicely with a multi-second exposure. It was also getting dark, with literally just a few minutes of light left in the sky, so I had to move quickly. This image was shot at F11 with ISO 100 for 20 seconds. Not incredibly long yet, but it was long enough for the clouds to move towards me, making this wonderful radiating pattern in the sky. This is accentuated of course because I was using a wide angle lens and the clouds closer to me appear to move faster than those in the distance. The 20 second exposure was also long enough to make the clouds in the valley blur making them almost look like a lake down there, behind the silhouetted foreground trees.

Step #2: Include a static anchor object

I find that long exposure images work well when you have something that will remain stationary in the image. It doesn’t necessarily have to be in the foreground, but if you don’t have something in the shot that doesn’t move, then the whole thing becomes a blur, and although that can work, it’s not going to be as powerful as having a rock solid anchor for the eye. In the image we’re currently looking at, the line of trees is the anchor. It’s a sharp, solid line for us to come back to, to keep everything in perspective, with that big sky adding drama to the scene.

Step #3: Use a sturdy tripod and good ball-head

Of course, if you are going to be doing long exposures, to keep the anchor object sharp, you’re going to need to keep your camera very still during the exposure and this requires a good sturdy tripod. One of the biggest mistakes people make when getting involved in photography is underestimating the value of a good tripod. It’s understandable, because when you first start out, you have the expense of getting a new camera, a few lenses, a camera bag, and these days if you don’t already have one you’re going to need a reasonably powerful computer and then there’s all the software. It seems to be never ending. So the last thing you want to spend a lot of money on is a $500 or even a $1,000 tripod. The problem is, at about the time you figure out why you need a tripod, you probably also find out that the one you picked up for $30 is about as useful as a chocolate frying pan. Don’t get me wrong, I did this myself. I’m right in there with you.

The game is still changing though, believe me. I thought I was doing just the right thing buying a nice Manfrotto tripod for around $450, and I stuck an Acratech Ultimate Ball-head on there, both of which are excellent pieces of kit, but when I moved from 12 megapixels with the 5D to 21 megapixels in the 1Ds Mark II and now also with the 5D Mark II, I found that with my longer lenses, like the 300mm F2.8, even my $450 tripod wasn’t quite cutting it. It had seen some wear though, but it was perhaps a bit small, and not really rated for such heavy gear either. The only way I could get things locked down enough for good sharp results in such high resolution images, was to buy a $1,000 Gitzo Tripod. The Acratech Ultimate Ball-head is still used from time to time on my second Gitzo Tripod, and it is a great ball-head, but my main ball-head right now is the Really Right Stuff BH-55. This is simply a work of engineering art. It not only operates beautifully, and locks the camera in position, stopping it dead with no effort, but it also looks and feels great. We can get into that in more detail in another episode though. The point is, buy the best tripod and ball-head or tripod head that you can afford, especially if you are going to be doing long exposure photography. If your camera gets blown around in the wind during the exposure you’ll end up with soft images.

Step #4: Use ISO and Aperture to go long, but beware of Diffraction

You should also use your lowest standard ISO for long exposures. Even if you are shooting in very dark conditions, set your ISO to the lowest standard setting, because if you start to bump it up, you’ll not only get shorter exposures, you’ll also start to introduce noise, where you really don’t want. Now, by the lowest “standard” ISO setting, I mean the lowest ISO rating that your camera has without going into any kind of expanded ISO. If your camera has expanded ISO settings, it usually means the manufacturer wasn’t comfortable making those ISOs available by default for one reason or another, so if ISO 100 is the lowest your camera goes to without you making any custom settings, then use that.

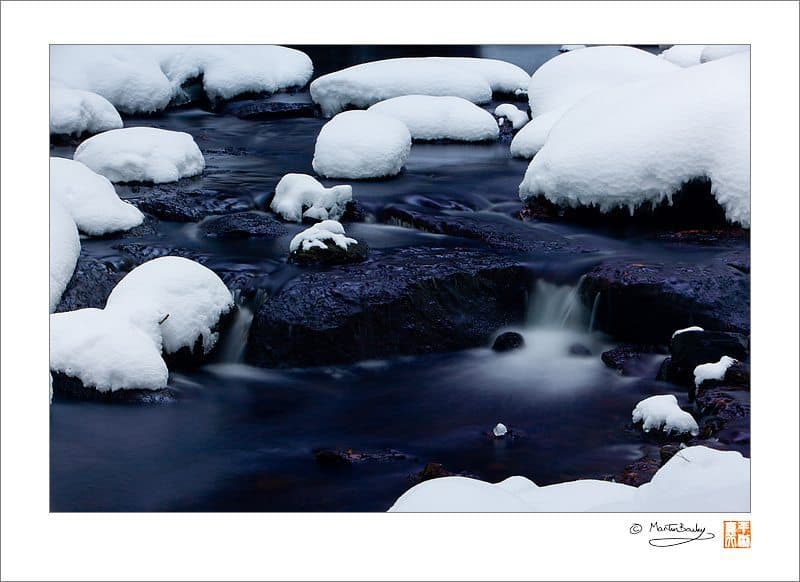

On my camera I usually use ISO 100 most of the time, but pretty much always unless I’m using the Highlight Tone Priority setting, in which case ISO 200 becomes my lowest ISO. Let’s bring up image number 1668, to help make this point. In this image, I was using Highlight Tone Priority to preserve the highlights in the snow. I don’t use Highlight Tone Priority much now, but at the time, that’s what I was thinking when I shot this image.

The next thing you’re going to want to think about is using a smaller aperture. Note though, that if you stop your lens down too much, you’ll find that diffraction starts to degrade your image. When we force light through a very small aperture, we start to lose resolution. It varies, but most lenses start to suffer from around F16. I generally tend to use down to F11, and only go as low as F16 when I really need to. F22 is for emergencies only in my book, and I only go there when I can live with lack of sharpness in my resulting image. I shot the first three images that we’ll look at today at F11 by the way.

Step #5: Use a Neutral Density filter when there’s still too much light

So, even when we have selected the lowest available ISO, and the smallest aperture that we are prepared to use, we sometimes still have too much light in the scene for the length of exposure that we want, and that’s when a Neutral Density or ND filter comes in. I’ll get back to what I used in the last image shortly, but for now, let me explain what an ND filter is. They are basically grey filters that cut out light without affecting the color balance of the image. They are rated with conveniently confusing numbers. An ND2 for example cuts out 1 stop of light, an ND4 cuts out 2 stops of light, and an ND8 cuts out 3 stops of light. There are much darker filters such as the ND64 at 6 stops, and the ND10000 at 13 stops etc. You may actually remember two wonderful PDF files that our good friend Landon Michaelson put together that we released with Episode 111. (Long Exposure PDF and Dark Frame Subtraction PDF). Well, I’m mentioning this right now, because the first document contains information on the various density filters and how many stops of light they cut out, so go back and check that for more detail.

Another type of ND filter that I should probably touch on before we move on, is the Vari-ND from Singh-Ray. This filter turns, a little like a Circular Polarizer, although contrary to common believe, it doesn’t simply use two polarizing filters to work. As you turn the filter though, you get a totally variable neutral density between 2 and 8 stops of exposure. Going back to the image we brought up earlier, I used a Singh-Ray Vari-ND filter in this shot to increase my shutter speed to 8 seconds. The Vari-ND is a bit expensive for what it is, and it can create some weird, unwanted effects with wide angle lenses in certain types of light, so it is not a magic bullet. But I find it works well with longer lenses, like the 70-200mm that I used here. I can’t remember exactly but probably dialed in about 6 stops of darkness for an 8 second exposure, which gave me this nice silky feel to the water in the shot.

Step #6: Take the guess work out of exposure

If you are using very dense neutral density filters, and you are working at a time of day when you can’t afford to do a multi-minute exposures only to find that you got it wrong and then the light is gone, you need to do a test first. The best thing to do is to meter and find your required exposure, maybe even shoot a text image, without the ND filter attached. Then when you are happy with the exposure, attach the filter and recalculate your exposure with the filter on. This will save you time, especially if your camera is using dark frame subtraction to reduce noise, and you’ll possibly also save yourself from making a mistake that could cost you your shot. You might recall that I mentioned an iPhone application called NDCalc back in episode 177. If you find the mental arithmetic difficult, NDCalc is perfect for calculating the new exposure in seconds, just by inputting your shutter speed before adding the filter and the density of the filter that you’ll attach.

Step #7: Focusing on what you can’t really see!

Focusing can be tough when it gets very, very dark. If you are working in normal light of course, and the darkness is coming from a very dense ND filter, the best thing to do is to focus before you put the ND filter on. If the front element of your lens rotates when you focus though, mind that you are careful not to rotate it when you attach the filter or you’ll throw your focus off. Even pushing on the front of the lens or grabbing the lens barrel can throw of the focus, so care is needed, but this will help you to focus while you can still see.

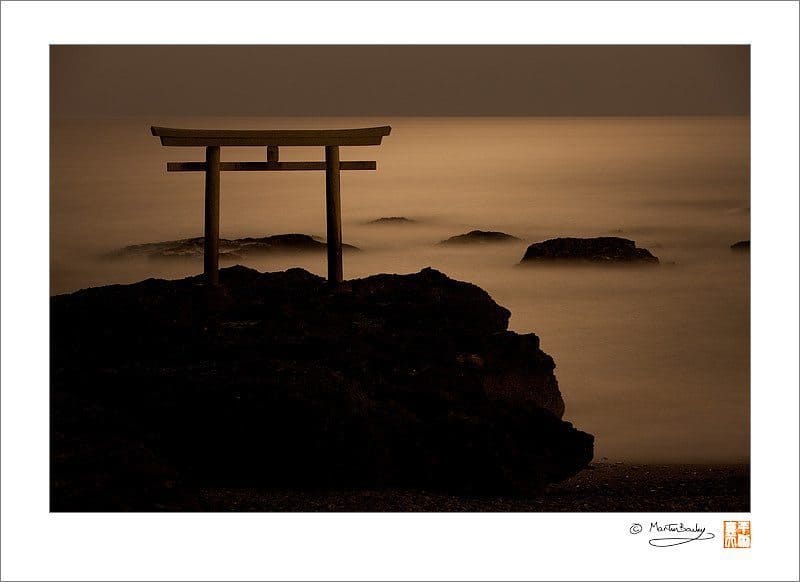

If it is already pretty dark, as it was when I shot the next image, number 2256, the chances are you no longer need an ND. Here I had some very faint light reflecting from the sea, but this exposure took four minutes at F8, so you can probably imagine how faint the scene was. I did a couple of things here though to focus, that I wanted to pass on to you. Firstly, through the lens, because there was a little bit of contrast, I could just about see when the outline of the main subject, which is the gate here. While turning the focus ring while looking through the viewfinder, I could just about make out the silhouette of the gate getting smaller as got into sharp focus. Once you go past the point where the focus is sharpest, it starts to get bigger again, so you just backtrack to where it was smallest and you’re there. If you have LiveView when you can faintly see, the image on the LCD can be noisy, but give it a try as well. Zoomed in to 5 times magnification, I could also see the outline of the gate getting gradually bigger and smaller as I moved in and out of focus.

If there simply is not enough light to focus visually, either through the viewfinder or on Live-view, you can try taking a powerful torch or flashlight, and actually throwing some light on your subject while you focus. If the light is powerful enough, it may even give your camera enough to auto-focus, but at the least, this should be enough for you to manually focus accurately. Be sure to actually switch your lens into manual mode though, especially if you use the default settings which have auto-focusing linked to your shutter button. You don’t want to manually focus then have the camera start to search for focus again when you go to trip the shutter. Also, if you are shooting with other people, you might mess up their photographs by shining a flashlight into the scene, so be aware of that. You could of course if you are alone use that same flashlight to do some light painting during your long exposure, which is fun, but that’s really another topic.

Step #8: Minimize camera shake with a cable release and mirror lockup

In addition to a good sturdy tripod, use a cable release or remote timer switch to avoid causing vibration with your hands when you press the shutter button to start the exposure. If you are using 30 seconds or less shutter speeds, you can use your camera’s timer, which will allow you to start the exposure, and then take your finger away from the camera, and allow any vibration to die down before the exposure starts.

If your camera has Live-view, and you use it, then you don’t need to worry about mirror lockup, because the mirror will already be up out of the way when you trip the shutter. If you don’t have Live-view though, or if at some point in the future the way Live-view works is changed, and that’s very possible because it’s still a new technology, you may need to set your camera to Mirror Lockup mode. This is basically where the first press of the shutter button makes your camera’s mirror jump up out of the way, exposing the shutter in front of the film or sensor, and then when you press the shutter button again, the shutter is opened and exposure starts. This helps to reduce vibration, caused by the mirror jumping up if you do that at the same time as you start the exposure. If you have a two second timer, you can often use this in conjunction with mirror lockup. What will happen is, if you set the two second timer and mirror lockup together, when you release the shutter, the mirror will lockup, and the two second timer will start automatically, and when the two seconds is up, the shutter is opened and the actual exposure starts.

Step #9: Use Bulb Mode

Most cameras’ longest shutter speed is 30 seconds. If you are going to go past thirty seconds, you’ll have to use Bulb mode, which is usually the B on the mode dial. This is basically where your camera’s shutter will stay open for the whole time that you are holding the shutter button down. Here, when I say shutter button, we’re talking about the button on the cable release, because remember, you don’t want to be touching your camera directly to start the exposure. You can hold the button down for the entire exposure, but most cable releases have a little slider that can be slid up or down, over the button once pressed, to stop it from lifting up again, effectively holding the button down for you. If you are timing your exposure, make sure that you use a stop watch with a beep when it gets to the time, or some sort of timer that will let you know when the time is up. If you use something like NDCalc that I mentioned earlier for the iPhone, not only does it help with the calculation of long exposures, but once you have the long exposure time displayed, you can start the count-down with the touch of a button on the display. It then plays a sound when the time is up, so you can stop the exposure manually. Of course before too long the iPhone will talk directly to the camera and stop the exposure for you, but we aren’t quite there yet.

The alternative to manually timing the exposure is a Timer Remote Controller like Canon’s TC-80N3, which allows you to dial in how many minutes and seconds, and hours for that matter, that you want it to continue to keep the camera’s shutter open. This is great for use in Bulb mode. You set the time of your required exposure, press shutter release on the Remote Controller, which is basically just a fancy cable release, and when the time’s up, the shutter closes. One other word of advice that kind of goes without saying, but I’m going to say it anyway, is when using bulb or doing really long exposure work, make sure you have fully charged batteries in your camera. It wouldn’t be much fun to get half way through a long exposure and your batteries die on you.

Step #10: Noise Reduction

Most cameras these days will by default automatically process images made with long exposures to remove noise. I find that the built in noise reduction in the camera and in Lightroom is enough for shots like the ones we looked at today. For this last shot, even with a four minute exposure, there was no real noise in the image after my camera had done its thing and Lightroom had applied its default noise reduction. Having said this, if you are shooting in warm conditions you can get more noise, and with longer exposures you can end up with a bit of noise. When I do have noise in my images, my favourite noise reduction software now is Nik Software’s Define, that can be found in the Noise Reduction package and the other Nik Software Suites. I also find that Noise Ninja from PictureCode does a good job of reducing the noise, and it’s highly configurable. There’s also a product called NeatImage, which is equally as good I believe.

Podcast show-notes:

Noise Ninja from PictureCode can be found here: http://www.picturecode.com/

NeatImage can be found here: http://www.neatimage.com/

Really Right Stuff are here: http://reallyrightstuff.com/

The Acratech Ballheads can be seen here: http://acratech.net/

The music in this episode is from the PodShow Podsafe Music Network at http://music.podshow.com/

Audio

Subscribe in iTunes for Enhanced Podcasts delivered automatically to your computer.

Download this Podcast in MP3 format (Audio Only).

Download this Podcast in Enhanced Podcast M4A format. This requires Apple iTunes or Quicktime to view/listen.

Great stuff Martin. I love listening to the podcasts, but having the transcript and images in one place like this too is awesome. Thanks for taking the time to type it all up!

Hi Richard,

Actually, 95% of the Podcasts start from the transcript, so I didn’t have to type this out just to post. I actually have over 1,000 pages of transcripts. There’s a book or two in there if I could make time to format it etc. 😀

I’m pleased you like having this all together like this. Most Podcasts are being released like this now by the way. I will post the odd archive transcript over time too. Stay tuned!